From Sacred Rituals to Global Stages: A Living History of Theater

Ritual Fires and Civic Stages

Theater did not begin with curtains rising or tickets sold. Its origins lie in ritual. Long before scripts or designated actors, communities enacted stories to explain the unexplainable. Anthropologists trace such performances to African and Indigenous traditions, where chant, dance, and mask blurred worship with storytelling. Marvin Carlson, in Theories of the Theatre (Cornell University Press), reminds us that drama was “a social act of representation long before it was an art form.”

In ancient Egypt, priests staged the Osiris mysteries, dramatizing death and resurrection in public ritual. These performances were not diversions but cosmic reenactments. Across the Mediterranean, Greece transformed performance into civic duty. Aeschylus and Sophocles framed tragedy as a forum for wrestling with justice, fate, and human agency. At the City Dionysia festival, citizens filled the Theater of Dionysus, carved into the Acropolis hillside, where attendance was less pastime than obligation. Imagine a democracy where showing up for Antigone was as essential as voting.

Asia’s Theatrical Blueprints

While Greece often dominates Western narratives, Asia was developing equally sophisticated performance systems. In India, the Nātyaśāstra (c. 200 BCE–200 CE) codified gesture, staging, and aesthetics with astonishing detail. It introduced the theory of rasa—emotional flavor—that still underpins Indian performance. Take Kalidasa’s Shakuntala: the goal was not only to narrate a love story but to immerse audiences in the bittersweet śṛṅgāra rasa, the essence of longing itself.

In China, shadow puppetry gave way to opera forms that layered music, acrobatics, and symbolic costuming. By the 18th century, Beijing Opera thrived as a fusion of art and politics. A flick of a sleeve could convey grief; painted faces encoded loyalty or betrayal. Meanwhile, Japan’s Noh theater (14th century) embraced stillness—slow movement, masks shifting expression with light. Kabuki, emerging later, reveled in spectacle: revolving stages, trapdoors, actors striking mie poses as the audience roared approval. Together these traditions remind us that theater was never one thing, but many—ritual, meditation, carnival, critique.

Rome, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance Reset

The Romans, great borrowers, adapted Greek theater into mass entertainment. Amphitheaters staged tragedies, but also gladiatorial combat and mock sea battles. When Rome fell, performance did not vanish; it changed shape. Medieval Europe turned to morality plays, passion dramas, and mystery cycles performed outside cathedrals, offering biblical lessons to largely illiterate audiences.

The Renaissance, however, set a reset button. Italian commedia dell’arte troupes roamed piazzas with stock characters—Arlecchino, Pantalone—improvising comic intrigues that laid groundwork for European comedy. England produced Shakespeare, who somehow blended sword fights for the groundlings with philosophical soliloquies for nobles. France pursued neoclassical unity—Molière slyly testing its limits—while Spain staged metaphysical baroque drama, as in Calderón’s Life Is a Dream. Across Europe, theater was no longer only sacred duty; it became a playground of wit, politics, and spectacle.

Crossings and Collisions in New Worlds

With colonial expansion, European theater spread, often displacing Indigenous forms but also creating hybrids. In Latin America, missionary dramas fused with local storytelling, birthing syncretic traditions. In the Caribbean, carnival performance turned masquerade into a form of survival and satire, reclaiming public space through music and parody.

In the United States, transplanted European models soon adapted to local rhythms. Vaudeville offered variety; minstrelsy—despite its racism—shaped the DNA of American popular entertainment. Broadway emerged as a laboratory for the musical, blending operetta, jazz, and spectacle. Show Boat (1927) broached race on stage, while Oklahoma! (1943) integrated song, dance, and story so seamlessly that the “modern musical” was born.

When Theater Started Looking in the Mirror

By the 19th century, realism became theater’s new frontier. Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House scandalized audiences by ending with Nora walking out on her husband and children. Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard shifted drama into pauses, silences, and half-spoken desires—real life rendered almost painfully ordinary.

Modernism soon pushed back. Bertolt Brecht, seeking to prevent passive consumption, developed Verfremdungseffekt—alienation effects—reminding audiences they were watching constructed drama. Antonin Artaud, in The Theatre and Its Double, demanded a “theater of cruelty,” designed to shake spectators to their core. Later, absurdists like Samuel Beckett staged emptiness itself: Waiting for Godot offered little plot, yet audiences sat transfixed by its haunting rhythms of futility.

Technology also reshaped performance. Electric lighting enabled subtle mood shifts; black box theaters dismantled rigid proscenium frames. Multimedia design blurred the boundary between live performance and cinema. Today, immersive companies like Punchdrunk (Sleep No More) invite audiences to wander multi-room sets, piecing together fragmented narratives like detectives.

Theater’s Global Pulse Today

Theater in the 21st century is plural, messy, and alive. Wole Soyinka merges Yoruba ritual with Western dramaturgy. Teatro Campesino in California uses performance as protest, staging farmworkers’ struggles. In Japan, directors remix Noh with contemporary dance; in the United States, artists like Suzan-Lori Parks and Lin-Manuel Miranda reinvent form and language to reflect shifting identities.

As performance theorist Richard Schechner has argued, theater is not just an event but a behavior—a way of gathering, of framing human action. Erika Fischer-Lichte, in The Transformative Power of Performance, notes how live theater produces a feedback loop between actor and audience, a co-presence unique to the form.

So is theater about catharsis, as Aristotle once claimed? Sometimes. But just as often it is about provocation, joy, resistance, or communal memory. Theater survives precisely because it absorbs change rather than resists it.

And perhaps that is its essence: from ritual bonfires to LED-lit stages, theater endures as humanity’s oldest technology for telling stories live. It is less about stages than about people—gathering, listening, watching, and, for a fleeting moment, believing together.

Similar Posts

10 Cities That Belong on Every Cultural Traveler’s Bucket List

Funding the Arts at Home, Pulling Back Abroad

Artists Are Not Being Replaced by AI—And the Fear Misses the Deeper Truth

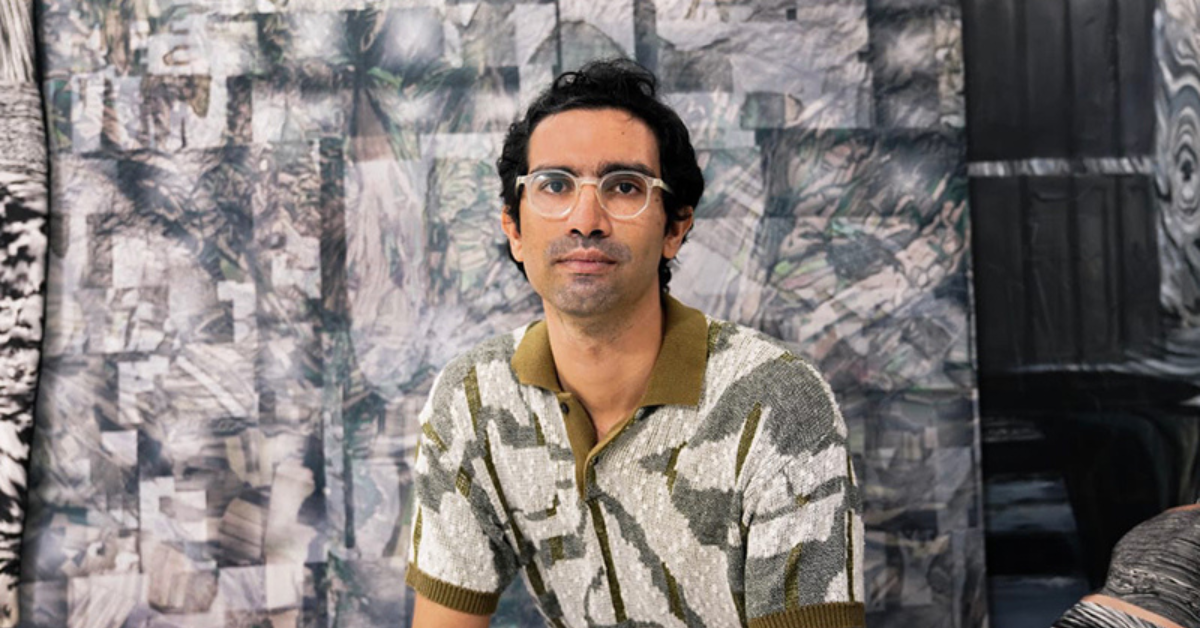

New World School of the Arts Alum Leonardo Castañeda Selected for the 2026 Whitney Biennial

Crossroads of Culture: Highlights from Art Basel Miami Beach 2025

Spotlight Series: Artists who took center stage during Miami Art Week

Savor the Season: Bulla Gastrobar Unveils a Spanish-Inspired Fall Menu

The Sound Inside Us: How Music Rewires the Mind and Restores the Soul

The Colosseum’s New Encore: From Gladiators to Global Music Stages

Experience World-Class Performances for Less with Tomorrow's Stars

Miami's Lincoln Road Turns Into a Free Open-Air Sculpture Garden for Miami Art Week 2025